PART III

Flags,

Lanterns, Rockets and Wires:

Signalling in the American Civil War

~ By ~

Lieutenant

Colonel Iain Standen

British Army, Royal Corps of Signals.

In the same way as aerial telegraphy ~ flagging and the other visual signalling methods required

some form of cipher, so did the telegraph. This was particularly important

as the telegraph was not beyond being intercepted. In September 1864 a rebel

operator got on a Union line pretending he was the regular USMT employee. Because

the interloper’s key signature was different, a USMT operator at another station

recognised what had happened and alerted the commanding officer. The latter

then fed the enemy operator misinformation about nearby Union forces. However,

to combat such attacks various methods of encryption were employed. In many

case considerable ingenuity and imagination were employed.

Below is one example thought to have been invented

by Lincoln himself.

“HEADQUARTERS ARMIES OF THE U.S., CITY POINT (VA)

8:30 A.M., April 3, 1865

To CHARLES A. TINKER, War Dept., Washington, D. C.:

A Lincoln its in fume a in hymn to start I army treating

there possible if of cut too forward pushing is he so all Richmond aunt confide

is Andy evacuated Petersburg reports Grant morning this Washington Sec’y War.

(Signed) S. H. Beckwith.” [12]

|

|

At first glance a jumble of words but when the main text is

read backwards with emphasis on the phonetics of the words rather than their

spelling all is revealed:

War Secretary, Washington

This morning Grant reports Petersburg evacuated Andy (and he) is confide

aunt (confident) Richmond all so (also). Is pushing forward too (to) cut of

(off) if possible there treating (their retreating) army. I start to hymn (him)

in a fume in its (few minutes).

A Lincoln

|

|

Other codes were also employed including the Court Cipher

we saw earlier, in a constant battle to keep secrets secret!

Whatever method was used to send a message, be it flags, lantern, rockets,

or telegraph there was still the issue of getting the message from the signal

station to the intended recipient. Therefore in order to disseminate the messages

there was a need to for local distribution capability. This invariably took

the form of couriers who would usually be mounted and would gallop off to the

appropriate headquarters to distribute a message once received and so complete

the deliver of the information process.

Campaign Examples:

Having looked at the how signalling developed and how it was undertaken,

the following will now pick out a number of examples of the use of signalling

during the Civil War in order to illustrate how the various aspects so

far discussed all worked together. Then, concluding this section with a slightly

longer look at the Battle of Gettysburg and the use of signalling during it.

First an example from the valley, and from the Confederate

Signal Corps. The Official Records of the Civil war include an interesting

debrief of a Master Sergeant S. A Dunning a confederate signal sergeant, who

surrendered to Federals in the Shenandoah valley in February 1865. I will read

the opening section of his debriefing and using this map try to highlight the

locations to which he refers:

Statement of Sergt. S. A. Dunning, Signal

Corps, C. S. Army, attached to General Early's headquarters:

I entered the Federal lines Thursday,

February 2. I had with me another man at Pitman Point, at the extreme end of

the Massanutten Mountain, near Strasburg. Have been there about two months.

We had a very fine glass (captured from the Federal Army), with which we could

look into the streets of Winchester. No force can leave Winchester or go to

Strasburg, Front Royal, Ashby's Gap, or Snicker's Gap, or in any direction,

without being seen, except at night or rainy weather. We were on post from 8

a.m. until 3 p.m. Usually we boarded with Mr. Braush Mackintosh, near the signal

station. My companion will think that I am captured, as I told him I was going

on a scout.

There is a chain of signal stations,

all connecting with New Market, from which place a telegraph goes to General

Early's headquarters [This was at Sperryvillle]; There is a station;

on the mountain at Ashby's Gap, one at Hominy Hollow, on Bock's Hill, near Front

Royal; one at Burnt Springs, on Fort Mountain, opposite Honeyville, at Ed. Browman',

between Burnt Springs and New Market Gap, and the station at Pitman Point. I

am perfectly familiar with the rebel signal code.’[13]

It would appear that he had a 24 man signal detatchment, which operated

from Pitman Point (sometimes referred to as Signal Knob) on Massanuttan Mountain

above Strasburg. They appeared to work in three shifts daily. Those not on

duty lived in a hotel at Burner's Springs (now 7 Fountains) in the Fort Valley

inside Massanuttan. The Warren County Historical Society once had the hotel

register wherein the proprietor kept an account for these troops for reimbursement

from the Confederate government. Here we see an excellent example of a fully

integrated intelligence gathering and communications system making use of both

visual signalling and telegraph.

It is perhaps worth making the point here that the Confederate

telegraph system was much less organized than the Union’s. There was a Military

Telegraph organization but like the Union’s staffed by civilians. It came under

the jurisdiction of the Postmaster General who for strategic reasons was put

in charge of all the commercial telegraphs within the Confederate States. In effect

the military telegraph just supplemented the existing telegraph infrastructure.

Unlike the Union, the Confederate Army did not have field telegraph capability.

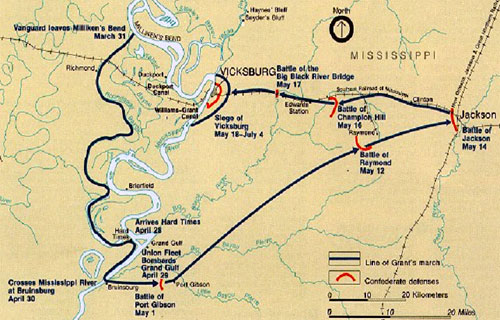

The second example is the

Vicksburg Campaign. The following will briefly run through how the

Union Signal Corps supported the Union Army in that campaign.

| The Vicksburg Campaign - 1863 |

|

|

On 7 April a line was opened from Grants HQ at Millikens’ bend through MacPherson’s

HQ to Osterhaus’ HQ at Richmond, and another pushed forward to New Carthage

. This system was used until the move forward to Grand Gulf. At this stage

all communication was by flag and in early May the senior Signal Corps officer,

Captain Ocran Howard telegraphed Myer for six signal trains i.e. field telegraph.

They were duly sent but did not arrive until after the fall of Vicksburg in

July 1863. On May 1st as the Battle of Port Gibson was being fought

a party of eight signal officers followed the Army forward and established signal

stations at Hard Times Landing, Bruinsburg and the shore opposite and ultimately

Grand Gulf. This network was put into immediate use supporting 17th

Army Corps’ crossing.

| Signal Deployment ~ Vicksburg |

|

|

Having consolidated itself in the bridgehead the Union Army moved out in a

North-Easterly direction. During this advance the US Signal Corps was very

much in the vanguard in its recent role. As the combat troops moved forward,

so did the signallers reporting back to their commanders and establishing stations

as they went at Raymond, Champions Hill and Bovina. Finally as the siege was

established round Vicksburg so a network of signal stations was also created

as we see here. These continued to provide important links between the various

parts of the Union force until the end of the siege on 4 July 1863. For its

work in this campaign the signal corps, and particular officers, received considerable

praise from the Union commanders.

My final example is the battle of Gettysburg, and I shall

look particularly at the US Signal Corps’ contribution in a little more detail.

| Gettysburg |

|

|

Early on the morning of July 1st 1863 Lieutenant Aaron B. Jerome the signal

officer of Brigadier General John Buford’s lst Cavalry Division stood alone

in the cupola of the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg. He had arrived

in town the day before having travelled north with the division, providing intelligence

by observation, and communications through his signal detachment’s use of signal

flags. Buford had arrived in Gettysburg the previous day and had sent Jerome

to watch for the enemy. On the 30th June he used the large cupola

of the Pennsylvania College but on the 1st July chose to occupy the

smaller, higher cupola at the Lutheran Seminary. From this vantage point he

had an excellent field of view and spotted the advanced pickets of Major General

Henry Heth's Confederate division as they approached from Cashtown. He immediately

sent one of his couriers with word of the advance to Buford, who then joined

him in the cupola to watch the approaching Rebels.

Leaving Jerome to his duties, Buford, realising the importance of the position,

placed his two cavalry brigades on both sides of the Cashtown Road, in a line

blocking the advance of Heth's division. Jerome was an experienced young officer

who had served at Antietam, where he helped man the Elk Ridge Signal Station

(a picture of which we saw earlier), to Chancellorsville, where his signal party

had swum the Rappahannock River, carrying field telegraph wire. His value to

Buford was such that on 27 August 1863 in his post-Gettysburg report the general

wrote the following:

‘Lieutenant [Aaron B.] Jerome, signal corps, was ever on

the alert, and through his intrepidity and fine glasses on more than one occasion

kept me advised of the enemy's movements when no other means were available.’[14]

He again reiterated

the same in a letter to Jerome in November 1863:

‘I have taken occasion to notice the practical working of the Signal Corps,

field, and regard it as a valuable auxiliary to an army. With the aid of their

powerful glasses, acting as both scouts and observers, the officers who have

acted with me have rendered invaluable service when no other means could be

availed. I regard their permanent organization as a matter of the first importance.’[15]

As the battle progressed, Buford’s troopers, fighting dismounted on the ridges

to the North-West of the town, held there own but were in danger of being overrun

by the superior numbers of Heth's infantrymen. Jerome, now rejoined by Buford,

spotted a large body of Union infantry approaching from the south on Emmitsburg

Road and identified it to Buford as Major General John F. Reynolds' First Corps

by, allegedly, reading the Corps' flag through his glass. Reynolds was accompanied

by a few staff officers and quickly went about the business of deploying his

troops. He had just placed Brigadier General James Wadsworth's division in

the line near the McPherson farm, when he was killed by a sharpshooter's bullet.

Jerome later recalled that Buford wrote a dispatch to Meade in the lieutenant's

notebook:

‘for God's sake send up Hancock, everything is going at odds, and we need

a controlling spirit’[16]

Later, from the cupola, Jerome could see Major General Oliver Howard's headquarters

party on Cemetery Hill, having just arrived and assuming command of the field.

He then saw Robert E. Rodes' Confederate division approaching Oak Hill from

the north and threatening to flank the First Corps' right. He therefore sent

the following message to Howard’s signallers

General Howard:

Over a division of the rebels

is making a Bank movement on our right; the line extends over a mile, and is

advancing, skirmishing.

There is nothing but cavalry

to oppose them.

A. B. Jerome [17]

| Gettysburg |

|

|

As Union forces retreated through the town Jerome moved position to the steeple

on the Gettysburg Courthouse from where he could see the signal station supporting

Howard's Eleventh Corps position on East Cemetery Hill. This station was maintained

by Captains Paul Babcock and Thomas. R. Clarke and subsequently moved to the

western part of Cemetery Hill, where Hall's battery was located, and on the

evening of July 1st became the central station in the network of

stations supporting Meade’s army.

During the 1st July the Chief Signal Officer of the Army of the Potomac, Captain

Lemuel Norton, remained at the Army headquarters near Taneytown. He had been

instructed by Meade to:

"…examine the line thoroughly, and at once upon the commencement of

the movement extend telegraphic communications from each of the following viz,

general headquarters, near Frizeliburg, Manchester, Union Mills, Middleburg,

and Taneytown road." [18]

Norton made arrangements to send the field telegraph trains forward, but they

were never deployed onto the battlefield. It should be remembered that at this

stage the Signal Corps still had control of its own telegraph capability. Norton

was keen to get to the battlefield in order to place the various corps signal

parties about the field. The signal parties had been assigned to each of the

seven corps in order to facilitate their movement north from Virginia. Norton

also had a reserve of eight officers with their non-commissioned officers and

couriers that he could place where he could best influence proceedings. However,

before he could carry out any deployments he was directed by Meade's Chief of

Staff, Major General Daniel Butterfield, that at dawn on July 2nd

he was to use this reserve to support the newly established headquarters.

In order to link the rear of the Army with the advanced headquarters near Cemetery

Hill he had posted a signal party at Indian Lookout, on the mountain behind

Emmitsburg, Maryland. Unfortunately because of the haze it was 11 p.m. before

communications were established, by torch, with the party on Little Round Top.

Meanwhile late on the night of July 1, a signal line was established from Emmittsburg

to Little Round Top, and on to Cemetery Hill. Early the following morning,

Lieutenant Jerome climbed the rocky northern edge of Little Round Top. Geary's

division had been removed to Culp's Hill and the signal party that had sent

torch signals to Emmitsburg had packed up and left with them. Jerome quickly

understood the importance of the position for signals and observation. Standing

on a large rock, he could see the Emmitsburg Road, Jack's Mountain, Cemetery

Hill, and General Meade's headquarters. Even without the use of his glass,

he could see signal parties occupying stations on Cemetery Hill and at Meade's

headquarters.

As Buford's troopers were occupying the area in front of Little Round Top and

serving as the screen for the left flank of Meade's army, Jerome could keep

his division commander informed of what he saw. However, he also realised the

importance of reporting anything significant to the signal party at the headquarters

station. He therefore began to observe the ground whilst his sergeant established

contact with the other two stations. Whilst Jerome was watching the battlefield,

Norton had arrived at the headquarters signal station, bringing the reserve

signal officers who had been at Taneytown. But upon arrival he found was pleased

to find that all the key sites on the battlefield had already been occupied

by officers who had arrived that morning or the day before in support of the

various corps. Therefore by midmorning on July 2nd, there were signal

officers on the Culp's Hill spur (now known as Stevens' Knoll), Power's Hill

where Major General Henry Slocum had his right wing headquarters, Cemetery Hill,

Little Round Top, and by the Widow Liester house where Meade’s headquarters.

The Headquarters was becoming very active as numerous couriers arrived with

messages from all parts of the field whilst General Butterfield, Meade’s Chief

of Staff, attempted to sort through the large amount of information as it arrived.

Meanwhile from his position on Little Round Top, Jerome continued to observe

the battlefield and shortly before midday saw Confederate skirmishers emerge

from the woods along Seminary Ridge. What he saw was three regiments of Alabamans

from Wilcox's brigade of Anderson's division. Jerome immediately told his sergeant

to send the following message to Butterfield:

Mountain

Signal Station

July

2, 1863,11.45 A.M.

General Butterfield:

Enemy Skirmishers are advancing

from the west, one mile from here.

Jerome, [19]

Minutes later Jerome saw Berdan's Sharpshooters under Lt. Col. Casper Trepp

come into contact with Wilcox's brigade. Jerome watched as Berdan's men fell

back toward the Union line and sent a second message to the headquarters:

Round

Top Mountain Signal Station

July

2, 1863, 11.55 A.M.

General Butterfield:

The rebels are in force, and

our skirmishers give way. One mile west of Round Top Signal station the woods

are full of them.

Jerome [20]

Shortly after Jerome sending this message, he and his party left with General

Buford, who had been ordered to Westminster and played no further part in the

battle. At about the same time Captain Norton began moving about the field

to ensure that all the necessary points were covered and accompanied by Captain

Peter A. Taylor, who had been assigned to the 11th Corps, went to

Little Round Top.

With the departure of Jerome they found Little Round Top unoccupied and began

to scan the field. They observed the movement of the rest of Anderson's division,

which had been camped a mile west of Herr Ridge, and sent the following information

to Captain Hall who was with HQ 11th Corps:

Round

Top Mountain Signal Station

July

2, 1863

Capt. Hall:

Saw a column of the enemy's infantry

move into woods on ridge, three miles west of the town, near the Millerstown

road. Wagon teams, parked in open field beyond the ridge, moved to the rear

behind woods. See wagons moving up and down on the Chambersburg pike, at Spangler's.

Think the enemy occupies the range of hills three miles west of the town in

considerable force.

Norton,

Taylor,

[P.S.]-This is a good point for

observations.[21]

Shortly after receiving the message, Hall joined Taylor on Little Round Top,

and Norton left to go back to the headquarters station. Hall was the senior

signal officer for the Eleventh Corps and as such took charge of the signal

station, and remaining there made significant observations during the afternoon.

At this time Major General Lafayette McLaws and his division were leading the

long column of Lieutenant General James Longstreet's Corps, closely followed

by Major General John B Hood's division.

The column marched along Black Horse Tavern Road. McLaws was proceeding along

with Captain S. R. Johnston, the guide provided to show the way around the flank

of the Union Army. However, shortly after Blackhorse Tavern Road crosses the

Fairfield Road, it ascends the crest of Herr Ridge. As McLaws rode to the top

of the ridge he immediately halted the column. He could see the large white

flag that the signal detachment was waving on Little Round Top.

Indeed if you travel that route today it is still very obvious just what a

commanding view the signal station on Little Round Top actually had. McLaws

therefore quickly looked for another route and not finding one rode back to

the column where he found Longstreet and said:

‘Ride with me and I will show you that we can't go on this route, according

to instructions, without being seen by the enemy.’[22]

This they did and McLaws insisted that the only way to avoid being seen by

the signal station was to counter- march. According to Col. E. P. Alexander,

now serving as Longstreet's artillery chief, this counter-march to avoid the

signal station cost the Confederates more than two hours in getting into position

opposite the Federal left. However, of all the officers in the Army of Northern

Virginia no two officers could be more qualified to realize the ability of the

signal station to obtain and transmit intelligence than Alexander and McLaws.

As you will recall Alexander had been a student of Albert Myer and had organized

the provisional Confederate Signal Corps, whilst McLaws had commanded a unit,

which Myer’s fledgling Signal Corps had supported during the western field trials

of the signal system in New Mexico in 1860.

At about 1.30 p.m Hall from his

vantage point at the Little Round Top signal station, spotted a large body of

Confederate soldiers:

"moving from opposite our extreme left toward our right." [23]

He signalled the information

to Butterfield at Meade’s headquarters. Some forty minutes later, he signalled

again with more information:

‘Those troops were passing on a by-road from Dr. Hall's House to Herr's Tavern,

on the Chambersburg Pike.’[24]

What Hall appears to have been observing was elements of Longstreet's command,

very probably McLaws' division, counter-marching. It is not clear whether Butterfield

or Meade understood the significance of this piece intelligence, since it indicated

that the movement was toward the Federal right and not in the direction from

which the attack eventually come.

At 4 p.m. Hall sent another message

to Meade’s headquarters stating that:

‘The only infantry of the enemy

visible is on the extreme left; [that is Federal left] it has

been moving toward Emmitsburg.’[25]

In his post-war report Brig.

Gen. Evander M. Law claims that this movement was the advance of his troops

into position just prior to his attack against Little Round Top.

At just after 4 p.m. Captains Hall and Taylor were alone with their signal

party on Little Round Top. They were then joined by Brigadier General Gouverneur

K. Warren, with his aides, Lieutenants Chauncey B. Reese and Ronald S. Mackenzie.

At his own suggestion Warren had been sent by Meade to recce the Round Tops.

It is not clear whether the messages about troop movements opposite the Federal

left had an impact on Meade's decisions to send Warren, but it certainly appears

that the by now he had considerable evidence that there was movement on his

left.

Two very different accounts exist of what actually took place on Little Round

Top that afternoon. The most quoted source is a letter from Warren to a Captain

Porter Farley dated July 13, 1872 in which Warren recalls that, with the exception

of a signal station, there were no troops on Little Round Top. He also states

that:

‘…this was the key of the whole position and that our troops in the woods

in front of it could not see the ground in front of them, so that the enemy

would come upon them before they would be aware of it.’[26]

Warren then states that he requested

that a rifled battery in front of the position (Smith's 4th New York) to fire

a shot and when they did so, Warren could see the

"glistening of gun barrels and bayonets of the enemy's line of battle."[27]

He makes no mention of the messages sent from Hall to Meade, or Butterfield,

or the fact that the signal officers told him that the woods were occupied by

Longstreet's men. The other version of events is provided by J. Willard Brown,

historian of the U.S. Veteran Signal Corps Association, and a friend and associate

of James Hall. According to Brown’s monumental history of the Signal Corps,

Hall had a difficult time trying to convince Warren there were Confederate troops

opposite the position, and I quote Hall’s version of events:

‘While the discussion was in progress the enemy opened on the station. The

first shell burst close to the station, and the general, a moment later, was

wounded in the neck. Captain Hall then exclaimed, 'Now do you see them?’ [28]

Conflicts in the accounts of survivors of Civil War battles were common, indeed

this is the case for most wars. Many of you will, I am sure, all recall Wellington’s

comment on the subject

‘The history of a battle in not unlike the history of a ball. Some individuals

may recollect all the little events of which the great result is the battle

won or lost; but no individual can recollect the order in which, or the exact

moment at which, they occurred, which makes all the difference as to their value

or importance.’ [29]

In truth the answer is probably somewhere in the middle of the two versions.

I find it difficult to believe Warren would come to the signal station and Hall

would not tell him of the troop movements he had observed. However, it would

not be unreasonable for a general to check this information by personal observation.

Regardless of which version is correct the fact is that Warren stayed near the

signal station as the battle for Little Round Top opened. Hall would leave

the position later that afternoon having been ordered to report to Major General

John Sedgwick.

In the meantime the other signal stations were also busy reporting intelligence

to the headquarters. At 4:35 p.m., Lieutenant. N. Henry Camp, who was set up

near HQ of Wadsworth’s Division on Cemetery Ridge reported sharpshooters in

the woods at the foot of Culp's Hill. He also reported at least two batteries

of artillery, which were not yet in position. Captain Edward C. Pierce and Lt.

George J. Clarke had marched from Westminster, Maryland, with the Sixth Corps

and arrived at Gettysburg at about 2 p.m. After waiting for some three hours,

the corps was positioned in support of the Federal left. Pierce learned that

the signal station on Little Round Top had been abandoned and decided to occupy

it. He and his men positioned themselves on the rocks (to the right of Hazlett's

battery) in the same spot Hall had occupied. As night fell on 2nd

July the battlefield, all of the key positions for signalling were again occupied.

At dawn on the 3rd July Captain Pierce and his party started observing the

field and began sending messages by couriers to Meade and various corps commanders.

The party could not use flags to signal because of the devastatingly accurate

fire from sharpshooters positioned behind the rocks at Devil's Den. Pierce

reported that seven men, including some officers, were killed or wounded near

the signal station. The Sixth Corps signal party was later joined by Lieutenants

J. C. Wiggins and N. H. Camp from the First Corps who also helped make observations

and used their couriers to send messages. Brigadier General Warren returned

to the signal station about 2 p.m. and tasked the signal officers with watching

specific points and reporting back to General Meade. Thus as Longstreet's soldiers

began to come out of the woods on Seminary Ridge to commence what is now known

as ‘Pickett’s Charge’ couriers from the signal station reported it to Meade's

headquarters which as a result of the Confederate cannonade was eventually forced

to move from the Leister House to Powers Hill.

After the repulse of the Pickett’s Charge, several corps commanders and Meade

visited Pierce and his signal party on Little Round Top. Indeed the station

was to remain active until July 6. Later in the evening of July 3, Meade again

moved his headquarters. It was established in a strip of woods on the Taneytown

Road, and a signal station was established there to maintain contact with the

other stations on the field. As the battle closed Captain Norton was busy placing

his signal parties so that they could make observations of the enemy and on

July 4, Hall moved into the town with Sergeants Chemberlin and Goodnough, and

climbed to the top of the courthouse steeple. He later moved to the cupola

on the Pennsylvania College and at 5:40 a.m. on July 5 he reported

‘…that the enemy had evacuated the position they held yesterday’ [30]

Norton terminated all of the signal stations with the exception of Little Round

Top, the Courthouse, Cemetery Hill, and Meade's headquarters and on July 6 all

the stations were discontinued as the army moved south toward Frederick. The

closure of the last signal station marked the end of signal activity at the

Battle of Gettysburg, although the signalmen would later make a significant

contribution near Boonsboro in support of the Army of the Potomac's pursuit

of the Confederates south of Hagerstown.

The Union Signal Corps' contribution during the Battle of Gettysburg

has been generally underestimated. It has long been agreed upon, that fear of observation,

from the Little Round Top signal station was the reason for Longstreet's counter-march

on the 2nd July. However the intelligence that the signal parties

provided to the senior commanders all over the battlefield is often not fully

appreciated. What is also important to remember is that the senior signals

officer present was only a captain and that considerable motivation, cooperation,

and dedication on the part of the signalmen was necessary in order to provide

the command structure with intelligence and command and control communications.

~ Lieutenant Colonel Iain Standen